The Clipeus Virtutis, Res Gestae 34, Aeneid VII and Augustus' Image

Coins are a welcome aspect of the OCR Classical Civilisation A-Level course, one (arguably) wrongly omitted as inessential from the old AQA. In this post rather than focussing on one of the set coins I have picked out a similar one to think through:Berlin, Pergamon Museum. Credits: Barbara McManus, 2005 minted in Spain, 19-18 BCE

http://www.vroma.org/images/mcmanus_images/indexcoins.html

Silver Denarius - RIC I, 36a

Augustus. 27 BCE-CE 14. AR Denarius (3.62 g, 6h). Spanish mint (Colonia Caesaraugusta?). Struck circa 19-18 BCE. Head facing right, wearing oak wreath / CAESAR AVGVSTVS, S P Q R above and below shield inscribed CL•V; laurel branches flanking. RIC I 36a; BMCRE 354 var. (laureate bust); BN -; RSC 51. (Image courtesy CNG) http://www.ancientcoins.ca/RIC/This coin is a good place to think through the ways that Roman Imperial Coinage cab carry meaning and inform us about the messages being disseminated and constructed through a variety of media in this period.

Legends

CAESARThe coin emphasises two names for the first Princeps, neither his by birth: Caesar he took as an inheritance from Julius Caesar in 44BCE and of it Antony is quoted by Cicero as saying, "et te, o puer, qui omnia nomini debes" " You boy, who owes everything to a name". The coin shows us very clearly that Augustus was continuing to emphasise this link some 26 years later.

AUGUSTUS

The name Augustus has even wider resonances. Suetonius tells us that in 27BCE:

Suetonius, Divus Augustus VII

...he adopted the name Gaius Caesar to comply with his great-uncle Julius Caesar’s will; while the title Augustus was granted him after Munatius Plancus introduced a Senate motion to that effect. Though the opinion was expressed that he should take the name Romulus, as a second founder of the city, Plancus carried the day, arguing that Augustus was a more original and honourable title, because sacred sites and anything consecrated by the augurs are called augusta. The custom is derived either from the ‘increase’, auctus, in their holiness, or from the familiar phrase avium gestus gustusve, ‘the posture and pecking of birds’ which this line from Ennius supports:

‘When with august augury illustrious Rome was born.’

So the name Augustus was both unique and new, and yet simultaneously reminiscent of the augury associated with Romulus, whose monarchic associations Augustus felt compelled to avoid. That the elite of his time were aware of the association between Augustus, Augury, Romulus is very obvious in Propertius:

Propertius IV.vi

Then he [Apollo] spoke: ‘O Augustus, world-deliverer…

acknowledged as greater than your … ancestors

conquer now by sea…

Free your country from fear…

Unless you defend her, Romulus misread the birds

flying from the Palatine,

he the augur of the foundation of Rome’s walls.

Brunt and Moore suggest in their notes to the Res Gestae:

SYMBOLISMS

The name Augustus should not be seen in isolation from the images on the coin. In 27BCE during the so called First Settlement, the symbols and name were granted to Caesar (hence forward Augustus) as a package of which he was immensely proud and about which he boasted in Res Gestae 34:

Res

Gestae XXXIV

In

consulatu sexto et septimo, postquam bella civilia exstinxeram, per consensum

universorum potitusrerum omnium, rem publicam ex mea potestate in senatus

populique Romani arbitrium transtuli. Quopro merito meo senatus consulto

Augustus appellatus sum et laureis postes aedium mearum vestitipublice

coronaque civica super ianuam meam fixa est et clupeus aureus in curia Iulia

positus, quemmihi senatum populumque Romanum dare virtutis clementiaeque et

iustitiae et pietatis caussatestatum est per eius clupei inscriptionem. Post id

tempus auctoritate omnibus praestiti, potestatisautem nihilo amplius habui quam

ceteri qui mihi quoque in magistratu conlegae fuerunt.

In

my sixth and seventh consulships, after I had extinguished civil wars, after by universal

consent, I was in control of all affairs, I transferred the republic from my power

to the control of the senate and the Roman people. For my service, by

senatorial decree,

I was named Augustus, and the doors of my house were publicly clothed in laurel,

and a civic crown [Corona Civica] were fixed over my door and a golden shield was put in the Curia

Julia, which was given to me by the senate and the people of Rome [SPQR] for my courage [Virtus],

clemency [Clementia], justice [Iustitia] and piety [Pietas], as attested by this inscription. After that time,

I surpassed

all in influence [Auctoritas] had no more power than those who were my colleagues

in the magistracies.

The package is all alluded to on this coin: We see the laurels associated with military victory; we see the oak wreath/Civic Crown showing him to have saved a life (or perhaps many Roman lives) being worn by Augustus on the obverse;

Brunt and Moore suggest in their notes:

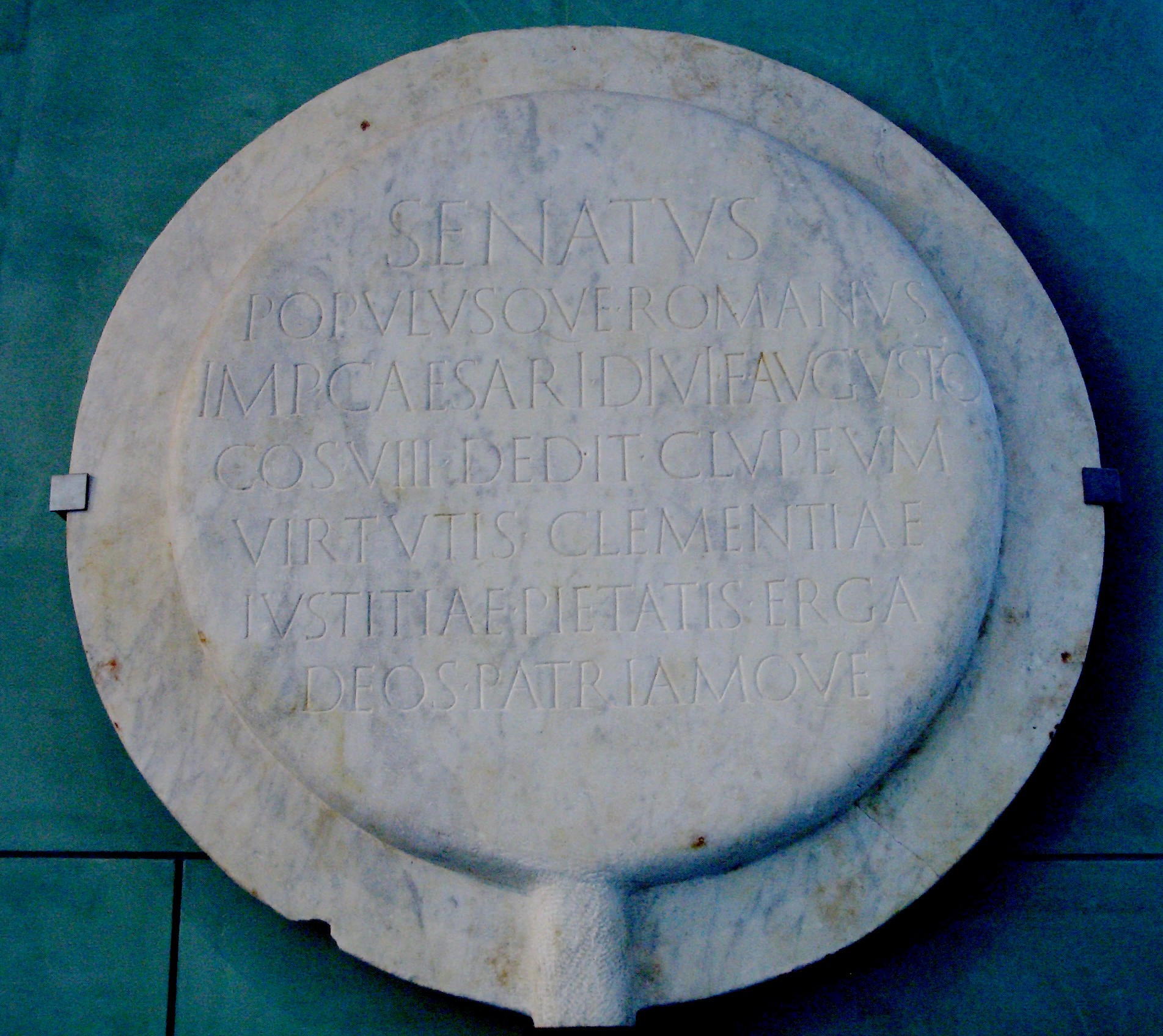

we see the name Augustus of course; we see the fact he was given this not by his own appropriation, but by the Roman Senate and People and of course we have the Clipeus Virtutis a copy of which was discovered in Arles

| http://www.livius.org/pictures/france/arles/clipeus-virtutis-of-augustus/ |

SENATVS

POPVLVSQVE ROMANVS

IMP CAESARI DIVI F AVGVSTO

COS VIII DEDIT CLVPEVM

VIRTVTIS CLEMENTIAE

IVSTITIAE-PIETATIS-ERGA

DEOS PATRIAMQVE

(http://www.socalcoins.com/collection/caesars/pages/AUGUSTUS_ric42a.htm)

Thus the coin is able to capture for us the whole package of awards and virtues he took and advertised. The combined effect of these was to demonstrate the Auctoritas, which is untranslatable, but means more than influence and has connotations of standing in the community.

As Augustus says the gold shield was placed in the Senate House, the Curia Julia, the laurel and oak wreath at his rather modest home on the Palatine and there it would be seen by the elite, but perhaps not by the masses who awarded it to him.

CIRCULATION

The coin is part of Augustus' ability to ensure that aspects of his programme of which he was proud were widely recognised. This coin from Spain, some eight years after the award, is playing up these symbolisms for an audience far removed from the Senate House as, in a less mobile way, is the marble version of teh Clipeus Virtutis above. The coin is one of many to show the Clipeus Virtutis and the ability to compress the shield's name to CL.V and omit any description suggests a wide familiarity with its content's meanings.

As a silver coin and one of many showing similar designs (the shield with a Victory was also popular) it seems reasonable to suggest that many tens or hundreds of thousands of people would be exposed to this image.

DESIGNED BY?

It is always tempting to speak of Augustus putting things on coins, but it seems inherently unlikely that the mint in Spain was being fed designs sketched by Augustus when bored between meetings. Rather there must be some form of diffusion of ideas in both directions: that which Augustus and those close to him emphasise is the subject local minters are tempted to create, but where images go wrong or are inappropriate the centre or a local may correct them. We see this in a later spanish coin showing Sejanus with Tiberius hurriedly slighted (see an excellent video here) or, in a related manner with the Senate offering Tiberius a range of honours after Piso's maiestas [treason]:

Tacitus, Annals III.18.ii

Likewise, when Valerius Messalinus proposed that a golden statue should be set up

in the temple of Mars the Avenger, and Caecina Severus an altar to vengeance, he demurred, insisting that such

consecrations were for foreign victories: domestic afflictions should be shrouded

in sadness.

So whoever designed this coin was at the least responding to the emphasis that was being placed on this honour from the centre and thereby contributing to that emphasis. We might compare this profitably with the coins celebrating Augustus' buildings. Did anybody have to tell the minters of coins that Augustus would be thrilled to have the temple of Mars Ultor with the standards he had retrieved from Parthia on coins, or did they notice that the temple and celebrations made this abundantly clear and thereby disseminate that message more widely than the temple itself ever could?

| RIC I 39b here |

VIRGIL'S AENEID

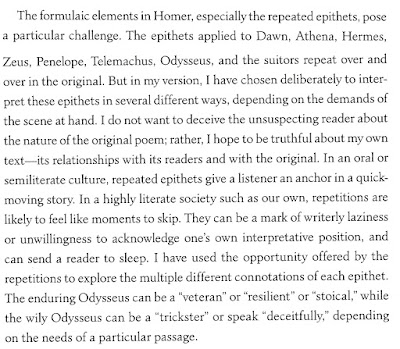

In a blog post I read recently here by Mike Fontaine some associations (covered up in OCR's specified West translation with ancile as "augural staff" rather than shield) are suggested as possible readings:

The Oxford Latin Dictionary certainly suggests West's translation has missed a trick here (note the associations with Mars too):

The authors, coin minters and people of Rome certainly knew Augustus' priorities and how important the images were to him; whether or not he was directing their imagery, playful allusions, etc. is more questionable.

.jpg/800px-Temple_Reliefs_at_Kalabsha_(I).jpg)