Cavafy, Homer and Augustus

The Greek Poet Constantine Cavafy (1863-1933) wrote on many themes (age, sex, place, and more) and very often wrote based on classical sources. I would like to look (briefly) at two.

Caesarion

Daniel Mendelsohn, from whose fabulous translation (available here) this is taken, adds in his notes:

Daniel Mendelsohn, from whose fabulous translation (available here) this is taken, adds in his notes:"Octavian (later Augustus) had Caesarion put to death; as he gave the order for the murder, one of his advisors is said to have complained sardonically of the dangers of polykaisariê, “too many Caesars.”

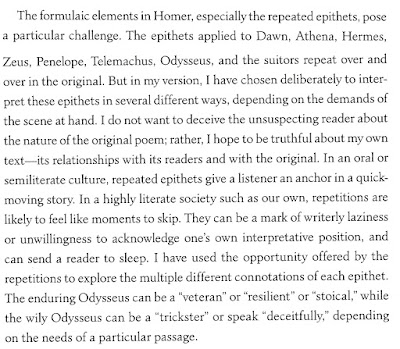

The Greek, polykaisariê, is a punning allusion to Homer's polykoiraniê, “too many rulers,” which appears in Homer’s Iliad, 2.203–6. In this famous passage, Odysseus berates the mutinous Greek troops who wish to abandon the siege of Troy and return home:

Not all of us Achaeans can be masters here;

too many rulers [polykoiraniê] is no good thing; let one man rule,

one king, to whom the crooked-minded son of Kronos gave the scepter and royal rights, that he may use them to be king."

Given the wars of words between Antony and Augustus prior to their clash in 31BCE at Actium, we might expect it to be Antony's children by Cleopatra who suffered, but in fact they seem to have survived. Caesarion was a threat because he too was apparently Julius Caesar's child; Antony declared him King of Kings and Caesar's heir!

Suetonius's account of the aftermath of Actium makes it clear why the clementia to be celebrated on the clupeus virtutis could hardly extend to Caesarion.

17 He returned to Italy [after Actium]... He stayed no more than twenty–seven days at Brundisium, just long enough to pacify the mutineers, then took a roundabout route to Egypt by way of Asia and Syria, besieged Alexandria, where Antony had fled with Cleopatra, and soon reduced it. At the last moment Antony sued for peace, but Augustus ordered him to commit suicide, and inspected the corpse. He was so anxious to save Cleopatra as an ornament for his triumph that he actually summoned doctors to suck the poison from her wound, supposedly the bite of an asp.

[compare Horace I.37 she scorned to be in the triumph & Propertius III.11 suggesting he saw her (effigy) in the triumph & Propertius IV.6 suggesting it would be shameful to have a woman led in triumph where once great men like Jugurtha were]

Though he allowed them honourable burial in the same tomb and gave orders that the mausoleum which they had begun to build should be completed, he had the elder of Antony’s sons by Fulvia dragged from the image of Divus Julius, to which he had fled with vain pleas for mercy, and executed. Augustus also sent cavalry in pursuit of Caesarion, whom Cleopatra claimed to be the son of Caesar, and killed him when captured. However, he spared Cleopatra’s children by Antony, brought them up no less tenderly than if they had been members of his own family, and gave them the education which their rank deserved. (Suetonius, Augustus 17)

With Caesarion and Cleopatra dead (on paper they had been co-pharaoh since 44BCE, though she was in charge), Octavian could get on with becoming the de facto Pharaoh himself (never took the title though)

18. About this time he had the sarcophagus containing Alexander the Great’s mummy removed from the mausoleum at Alexandria and, after a long look at its features, showed his veneration by crowning the head with a golden diadem and strewing flowers on the trunk. When asked, ‘Would you now like to visit the mausoleum of the Ptolemies?’ he replied, ‘I came to see a king, not a row of corpses.’ Augustus turned the kingdom of Egypt into a Roman province, and then, to increase its fertility and its yield of grain for the Roman market, set troops to clean out the irrigation canals of the Nile, which had silted up after many years’ neglect.

.jpg/800px-Temple_Reliefs_at_Kalabsha_(I).jpg) |

| Augustus annointed by Egyptian gods |

So this young man of 17 had to die. Cavafy notes how few lines there are describing him in history and very few certain images. He plays with the flattery of the court "unstinting laudations" and with the cruelty of Octavian as history records, but uses the gap where history is silent, about the young man's appearance, character, etc. to play with a more homoerotic image of his being visited by an image of the prince when the light went out "I let it go out". Art exists in and exploits the gaps in history.

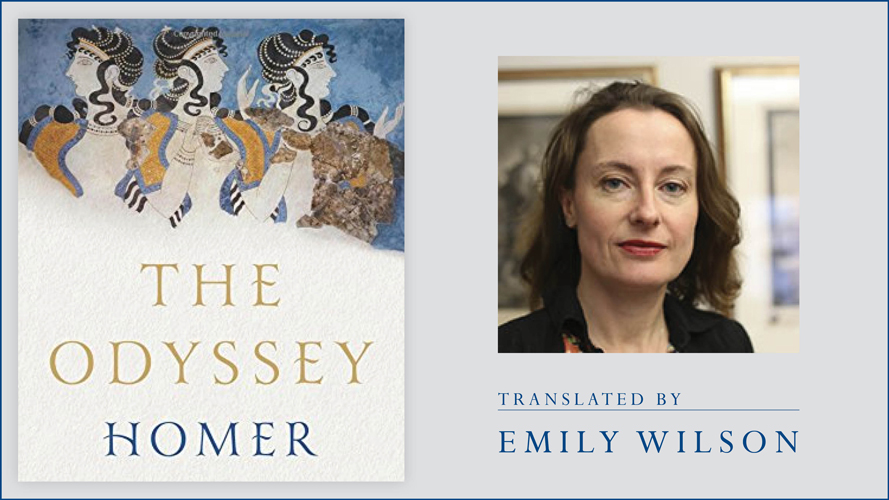

ITHACA

Cavafy's use of the Classics is also to be seen in perhaps his most famous poem, his reworkings of Odysseus's journeys in Ithaca. This poem is also available spoken by Sean Connery. In this poem you will notice (again in Mendelsohn's translation) how Cavafy takes the stories of the Odyssey and allegorises them.

This poem is also available spoken by Sean Connery. In this poem you will notice (again in Mendelsohn's translation) how Cavafy takes the stories of the Odyssey and allegorises them.The Laestrygonians, Cyclops, Poseidon are none of them beings, but our own mental blocks and the issues you allow your soul to "set up before you".

The journey of Odysseus becomes an allegory for a life lived to the full travelling through Egyptian Alexandria (Cavafy's home) and Phoenicia with Ithaca never the reward we strive to reach, only the endpoint.

In some ways this plays with Tennyson's poem Ulysses which imagines Odysseus bored by the humdrum Ithaca.

"Ithaca gave you the journey"

This way of reading Homer is by no means unique, many writers have recognised the psychological possibilities of aspects of the Odyssey. Tantalus has entered English as our experience of wanting that which is just out of reach,

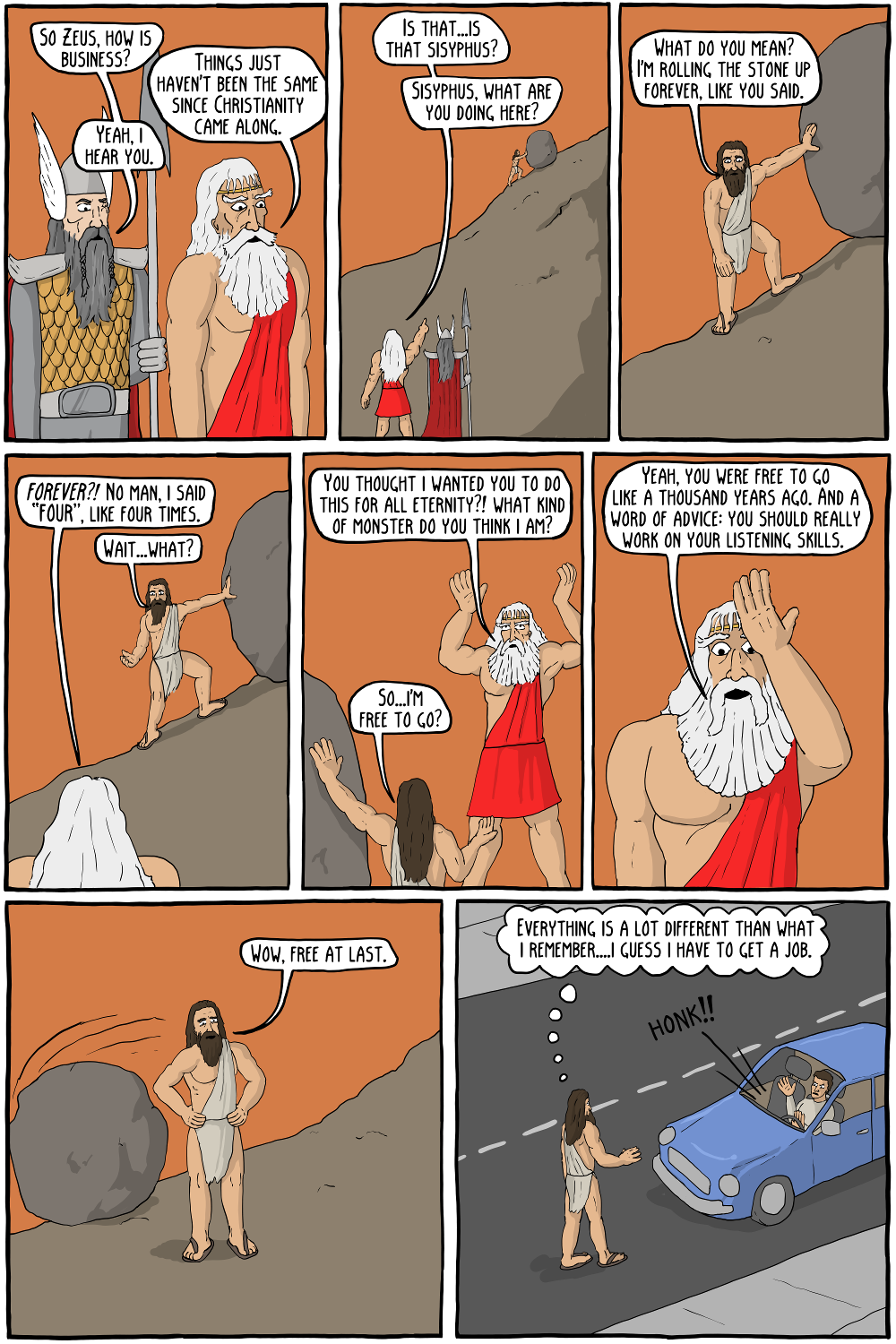

Sisyphus has entered English as Sisyphean meaning a task too hard for our endurance and as a model of pointless, but endless, even absurd, endeavour.

The Sirens of course are divorced from their original offering of knowledge and made erotic and tempting in everything from paintings to children's films.

|

| Herbert James Draper Sirens and Ulysses |

Of course they also leave room for humorous reworkings:

|

| https://existentialcomics.com/comic/110 |