Clementia (mercy)

Writing of the First Settlement in 27BCE Augustus says:

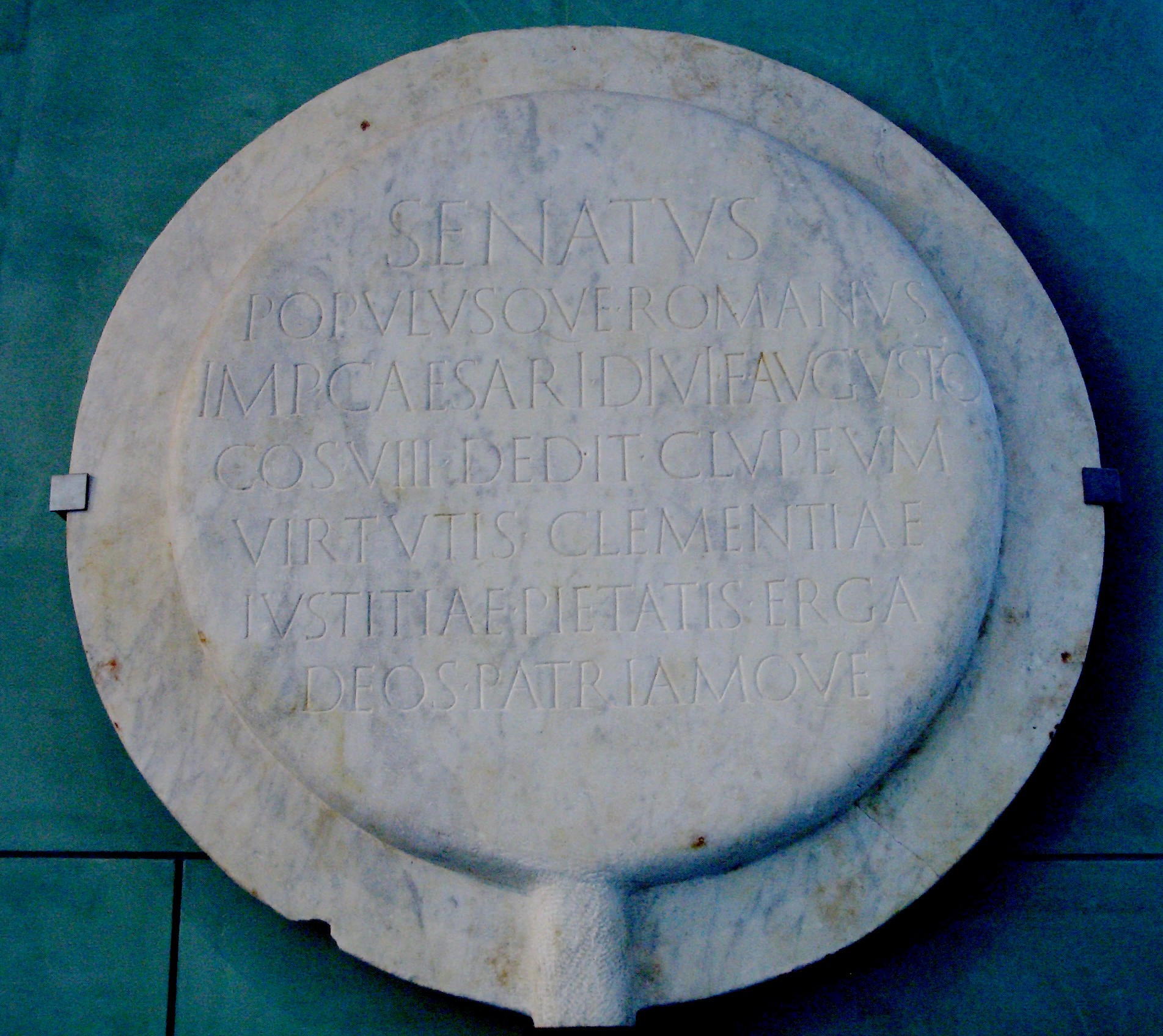

"...by senatorial decree, I was

named Augustus, and the doors of my house were publicly clothed in laurel, and

a civic crown were fixed over my door and a golden shield was put in the Curia

Julia, which was given to me by the senate and the people of Rome for my

courage, clemency, justice and piety, as attested by this inscription. After

that time, I surpassed all in influence, although I had no more power than

those who were my colleagues in the magistracies." (Res Gestae 34)

mihi senatum populumque Romanum dare virtutis clementiaeque et iustitiae et pietatis caussa testatum est per eius clupei inscriptionem. Post id tempus auctoritate omnibus praestiti, potestatisautem nihilo amplius habui quam ceteri qui mihi quoque in magistratu conlegae fuerunt.

mihi senatum populumque Romanum dare virtutis clementiaeque et iustitiae et pietatis caussa testatum est per eius clupei inscriptionem. Post id tempus auctoritate omnibus praestiti, potestatisautem nihilo amplius habui quam ceteri qui mihi quoque in magistratu conlegae fuerunt.

|

| maarjaara [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

Clementia was not always very much in evidence during the civil wars and proscriptions:

|

| Suet. Div. Augustus |

CLEMENTIA as AUTOCRATIC and MONARCHIC

SENECA on CLEMENTIA

To offer clementia (mercy) is not within the reach of normal people because it requires that you explicitly give less punishment than is required by justice and law. Seneca writing of Clemency in the middle First Century says, "None is better graced by mercy than a king or a prince (quam regem aut principem)"(de Clementia I.2.iii) and further notes in the voice of the ruler "anybody can kill against the law, but no one other than I can break it to save (Occidere contra legem nemo non potest, servare nemo praeter me)" (De Clementia I.v.4). That is, he explicitly links this ability to step outside the law with the power of monarchs and princes.

So, whilst Augustus is boasting, "I had no more power than those who were my colleagues" he is simultaneously advertising his ability to do less than the law demanded (and so be above or outside it). Exactly why he chooses to advertise this virtue in the same breath as describing his powers as limited to the levels of senatorial colleagues I am unsure and thinking about.

LEX DE IMPERIO VESPASIANI

In the Capitoline Museum you can see a law granting Vespasian (the emperor from 69-79CE) his powers.

|

| https://droitromain.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/Anglica/vespas_johnson.html |

The exemption from laws, which is tracked back to Augustus (though given how much his position changes through 43BCE-14CE, it is not obvious when this means or even if it is true), identifies perhaps the nature of Imperial power - the laws which bind others, do not have to bind them.

TIBERIUS - autocracy

Under Tiberius the problem that Clementia indicates a princeps being outside/above the law becomes very pronounced. I want to think and read more about this, but you might think about:The aftermath of Libo Drusus' trial, where Tiberius stated he would have intervened AFTER due process had happened had he not committed suicide (Tacitus Annals, II.27-32)

Urgulania's trial, where Tiberius undertook to appear for his mother Livia's client, but in dismissing the Praetorian Guard to a distance publicly showed he intended to appear as a privatus (private citizen), not as the Princeps, with attendant powers to stand outside the law. (Tacitus Annals, II.34)

Clutorius Priscus' trial, where Tiberius' desire to show clementia is flagged by Lepidus and Tiberius seems to have required a ten day delay in future between legal condemnation and execution to allow room for him to exercise Clementia and overturn legal process. (Tacitus Annals, III.49-50)